Cycles and Movements:

A Year in the Life of a Seal

Illustration by Katelyn Gonsalves

Gray seals, harbor seals, harp seals and, occasionally, hooded seals visit the shores of Massachusetts, Maine, New York, and beyond. But how do you identify WHAT seal are you seeing?

Every seal species has a unique and distinct life history. Here, we focus on gray and harbor seals, which are our most common seals in New England. Both live, breed, and molt in the Northwest Atlantic (from a land-based perspective, this means the East Coast of Northern North America), but the specifics of their lives keep them amazingly separate.

The Molt

Gray and harbor seals give birth and molt at different times of the year. Both times (breeding, moulding) are energetically costly.

“The molt” is when seals completely replace all the hairs/fur on their bodies, which harbor and gray seals do every year. “The molt” is an intense time for a seal.

During molting, seals come ashore in large numbers to rest and push out a whole new coat of hair. It takes about three weeks to shed and regrow all the hair on their bodies. Because of this intense, energetic work, seals need to rest on shore while they are molting.

For Gray seals, moulting happens in March-May; for harbor seals, it’s June-August.

Watch this animated video to learn more about the gray seal molt.

Following Seals From Afar: Satellite Tags

Gray and Harbor seals can easily swim distances of several hundred miles—they can even sleep at sea.

Satellite tags placed on harbor and gray seals helps researchers and managers understand where seals and human activities at sea—fishing, U.S. Navy and military activities, shipping, wind farms, and more—might overlap and impact seal behavior. However, the data is not perfect.

It’s very hard to put a satellite tag on an adult gray seal, so most of the tagged seals are pups of the year or rehabilitated seals. All the same, the stories behind the movements of tagged seals are hugely moving and important.

How do you put a satellite tag on a seal? With glue. The tags, which only transmit when in air, are glued to the seal’s “shoulders.” When seals molt, as they do every year, the tag is shed.

Gray Seal Satellite Tag Movements

Tracks of two gray seal pups tagged on Muskeget Island, Massachusetts in January 2019 by the Atlantic Marine Conservation Society and partners at the Northeast Fisheries Science Center Seal Ecology Program under NMFS permit #21719. Tracks show approximately 6 months of data. Virginia pinniped tagging study funded by U.S. Fleet Forces Command as part of the U.S. Navy Marine Species Monitoring Program.

The tagged seals went south to the Chesapeake Bay and north to Nova Scotia, sometimes staying nearshore and at other times heading to the continental shelf, showing the wide movements of gray seals.

What does a satellite tag look like? The image below is of “Bronx,” a young gray seal who was disentangled, rehabilitated, and then released. The tag is put on the seal’s back with epoxy, and a seal will shed the tag when they molt, as gray seals do each spring.

To transmit, the tag needs to be above the water, which is why tags are placed high on a seals’s back.

IFAW

Harbor Seal Satellite Tag Movements

Tracks of 3 harbor seals tagged in 2018. Pink and yellow lines show movement of seals tagged in Virginia under NMFS permit #17670. Virginia pinniped tagging study funded by U.S. Fleet Forces Command as part of the U.S. Navy Marine Species Monitoring Program.

During 4-6 months of tracking, one seal stayed relatively local to its tagging location, while the other traveled to the coast of Maine. The blue line shows the movement of a harbor seal pup released in Long Island Sound in October 2018 after rescue and rehabilitation by Mystic Aquarium, Marine Mammals of Maine and the Atlantic Marine Conservation Society. During only 5 weeks of tracking, the seal traveled to Nova Scotia and back. Data provided by Whalenet.org.

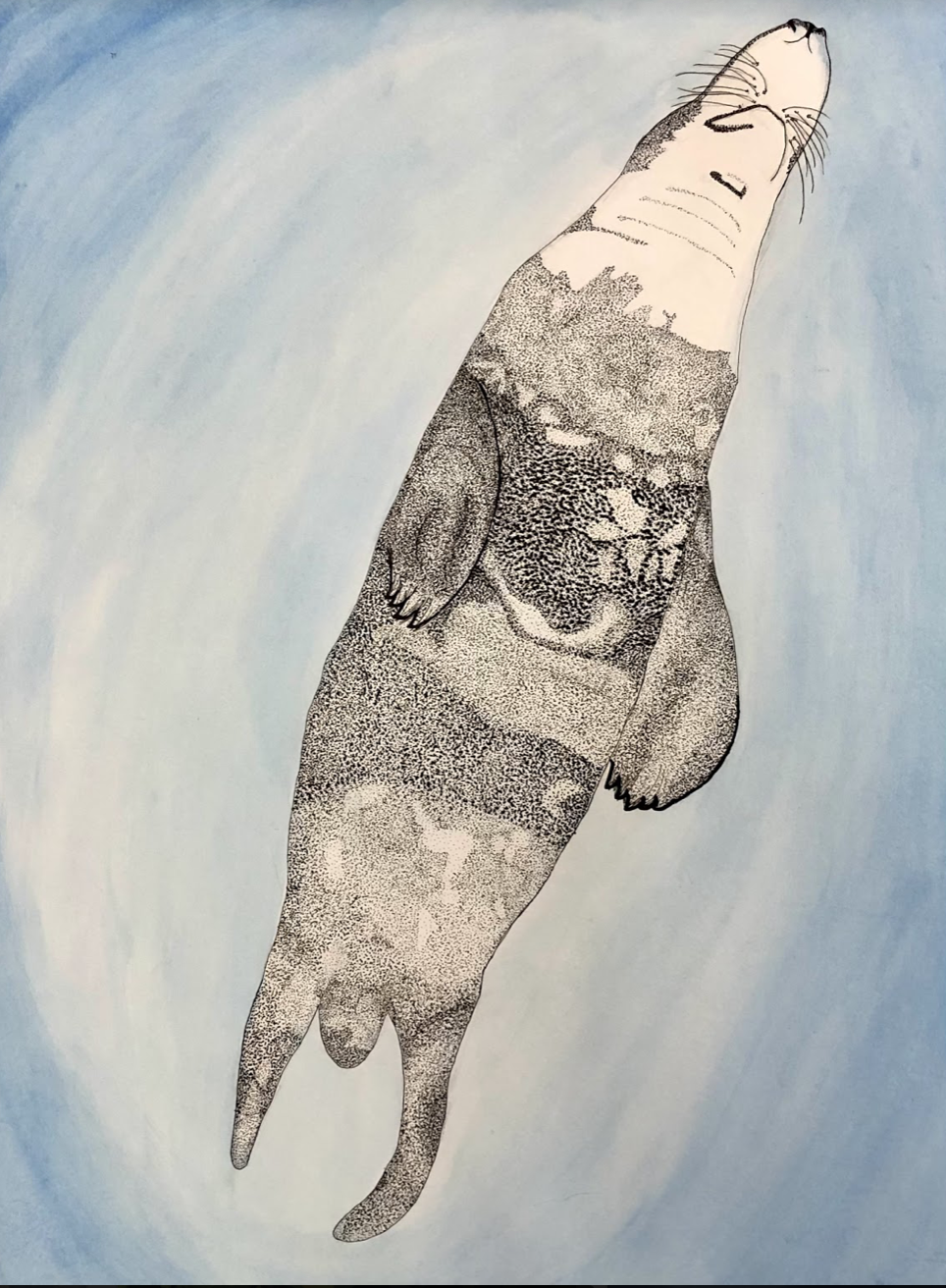

Below, you can see a “tagged” seal from above. The goal is to have the tag be small and unobtrusive enough that it does not interfere with a seal’s day-to-day activities.

Monica DeAngelis NMFS permit #21719

References/Dive Deeper

“Tagging Gray Seal Pups,” WHOI

Video: The Science of Seal Tracking, Featuring Monica DeAngelis

https://www.navymarinespeciesmonitoring.us/index.php?cID=479